PhD in numbers

In the near end of my PhD, as a quantitative ecologist, I thought it might be fun to visualize some PhD statistics. Here I am gonna show the record of paper rejections, the diversity of the journals I published in, and the time series of email exchanges with my advisor.

Paper rejections

No scientist can run away from rejections. I got a lot of rejections during my PhD. Not only papers but also award and fellowship applications. It still hurts whenever I get a rejection, but it is less painful than the beginning.

As an early career researcher, I appreciate it when people are brave enough to share their rejections. It helped a lot to overcome my Imposter Syndrome when I started grad school. As Melanie Stefan has eloquently argued in her post, it is important to build an academic culture where people don’t feel uncomfortable in sharing their failures. I am glad that many researchers have helped to move towards this goal. For example,

- Twitter. #rejectionistherule is a popular hashtag in academic Twitter, where many big names in ecology would share their stories of rejections.

- Blogposts. Many ecologists have blogged about this topic (e.g. blog post; blog post).

- CVs of failures. Such as here.

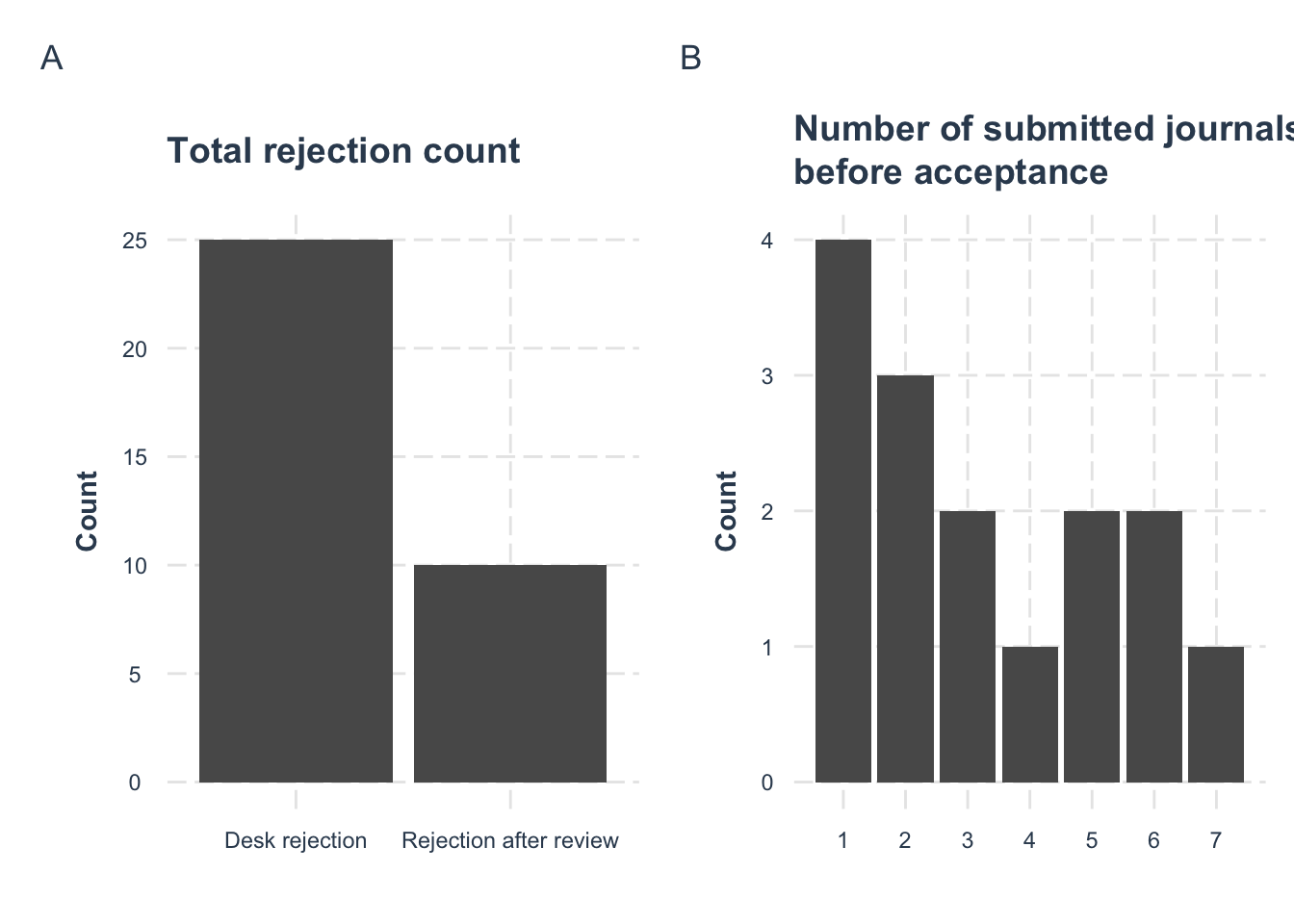

Since I happen to keep a track of the submission history of my papers, I’d like to join the forces into sharing my rejection records. In total, I got 35 rejections(!) where 25 are desk rejections and 10 are rejections after peer review (Panel A). And as for each paper, it can take from 1 journal to 7 journals before it got accepted (Panel B).

On a side note, I don’t find that the papers that went through more journals have lower qualities than those got accepted quicker. Also, I don’t think that these papers have climbed down the journal ladder. Of course, I am obviously biased and don’t have any objective way to measure the quality. This would be a topic for the research field called the Science of Science. Some researchers have done rigorous analyses on this topic (such as this).

Journal diversity

We love diversity as ecologists. Thus, I checked the diversity of the journals I published in. I published 12 peer-reviewed papers in 12 journals so far. I was surprised to realize that I never published in the same journal (the only exception was a response paper to a comment, which was not peer-reviewed). I did not deliberately aim to diversify the published journals. Then, was this simply a beautiful coincidence or more because of my submission trajectories?

I need a null model to answer this. For the null model, I simply assume that I have had an equal chance of publishing in any journals I submitted except the lottery journals. Then I use the Simpson’s index to measure the diversity, which tells the likelihood of randomly picking two papers and they happen to be in the same journal. My empirical Simpson’s index is 0. The figure below shows the simulated distribution of the Simpon’s index under the null model. It shows that it is extremely unlikely that I would get the empirical journal diversity under the null model.

Of course, it is debatable whether this null model makes sense. The rationale behind this null model is the stochasticity in the publishing game. For a paper to appear in a particular journal, there are two inevitable sources of uncertainties: the associate editors and the reviewers. No paper would be liked by everyone, thus, the randomness in whom the papers were edited or reviewed would determine the outcome. Experiments have already confirmed the stochasticity (e.g. this experiment and this analysis with surprising results).

Putting it into a broader context, one nice thing I love about the ecology community is the lack of a strong hierarchy of journal prestigiousness The randomness in the publication game exists in every research field. Thus, a very strong hierarchy of journal prestigiousness can be disastrous for an unlucky researcher. Ecology has many good journals that (at least to me) I would be equally happy to publish. Thus, a paper is still likely to end up in a decent journal even with bad luck in several other decent journals.

Email exchange

Our research group does not use Slack, so we primarily exchange research-related stuffs via email. Thus, the number of email exchanges might be a rough indicator of my research activity. This motivated me to take a look at the time series of email exchanges with my advisor, an analogy to the seasonality or the phenology analysis in community ecology.

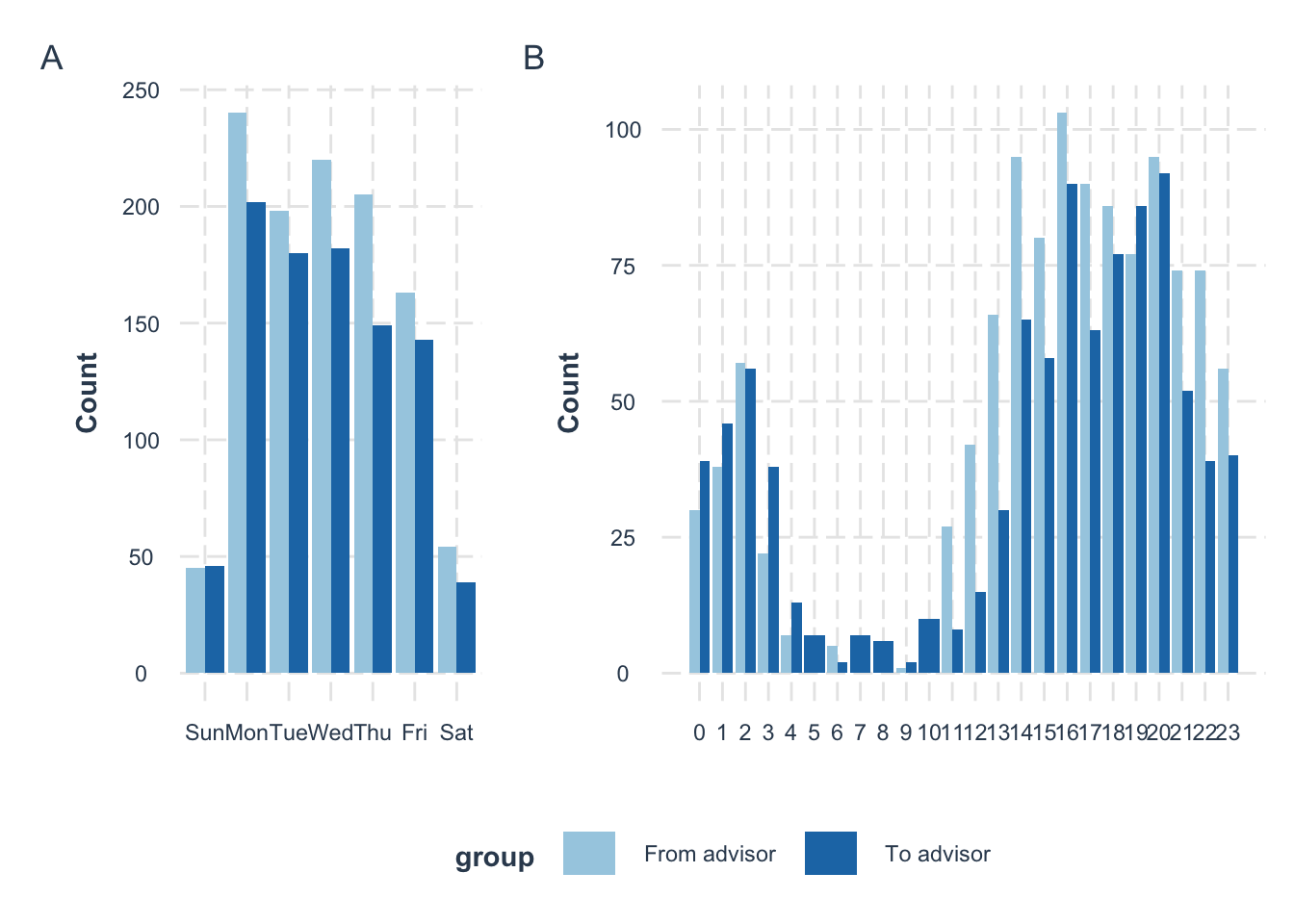

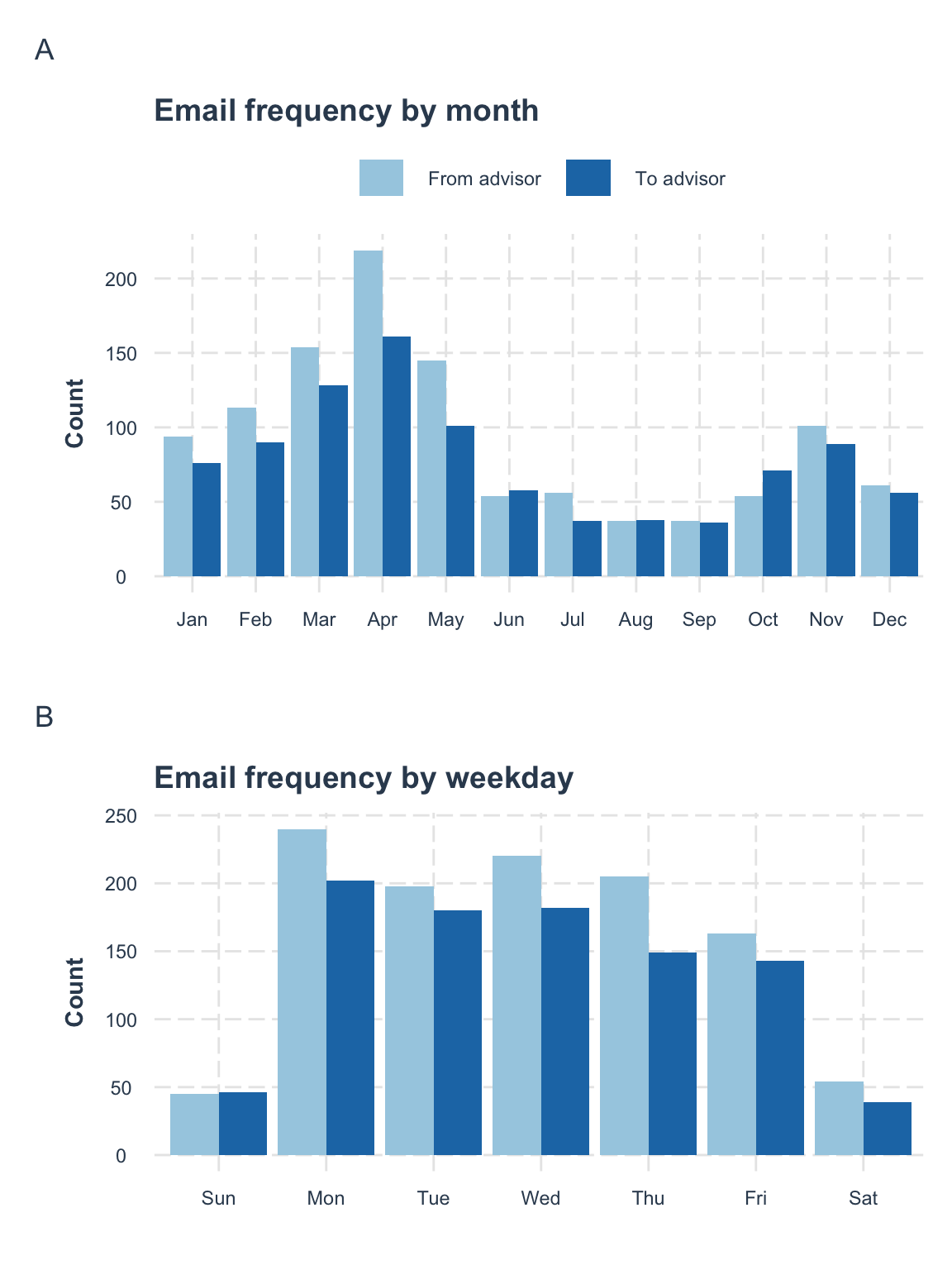

In total, my advisor sent me 1125 emails while I sent him 941 emails (which occupies about 40\% of all emails I sent during the grad school). In general, my advisor and I have similar patterns of email frequencies, which was not surprising since we generally reply to each other. Then I divide them into month (Panel A) and weekday (Panel B):

- Focusing on month, while I expected that my research activity would drop in the summer, I was surprised to see that I am more lazy in the Fall than in the Spring.

- Focusing on the weekday, it is clear that I am becoming lazier towards the weekends :D

Keywords of my research

I made a word cloud based on the word frequencies in my papers. I am happy to see that my works are more ecological than mathematical. So I guess I can call myself an ecologist now :)